Reading time: 7 minutes

From the bleaching privilege to textiles for Boeing and Airbus

Under the motto “C the Unseen,” the German city of Chemnitz is presenting itself this year, together with 38 surrounding municipalities, as the European Capital of Culture. Following West Berlin, Weimar and Essen, this marks only the fourth time that Germany has held this title. The anniversary programme features over 1,000 exhibitions, projects, events, festivals, free walking tours and workshops, designed to highlight the region’s unique strengths – in Chemnitz, above all, its textile industry, with roots reaching back to the 14th century.

From the bleaching privilege to “Saxon Manchester”

In 1357, Margrave Frederick III of Meissen issued a seemingly minor but far-reaching document: the bleaching privilege.1 It granted four Chemnitz citizens the exclusive right to establish a national bleaching site on the River Chemnitz, north of the city. Within a 75-kilometre radius, only they were permitted to bleach textiles – mainly linen at the time. This privilege is now considered the birth certificate of the Chemnitz textile and apparel industry, transforming what was then a small town into the region’s central hub for textile trade and distribution. By the 17th century, over a third of the population worked in textile-related trades such as weaving, dyeing, spinning or cloth making. But the bleaching privilege was only the beginning.

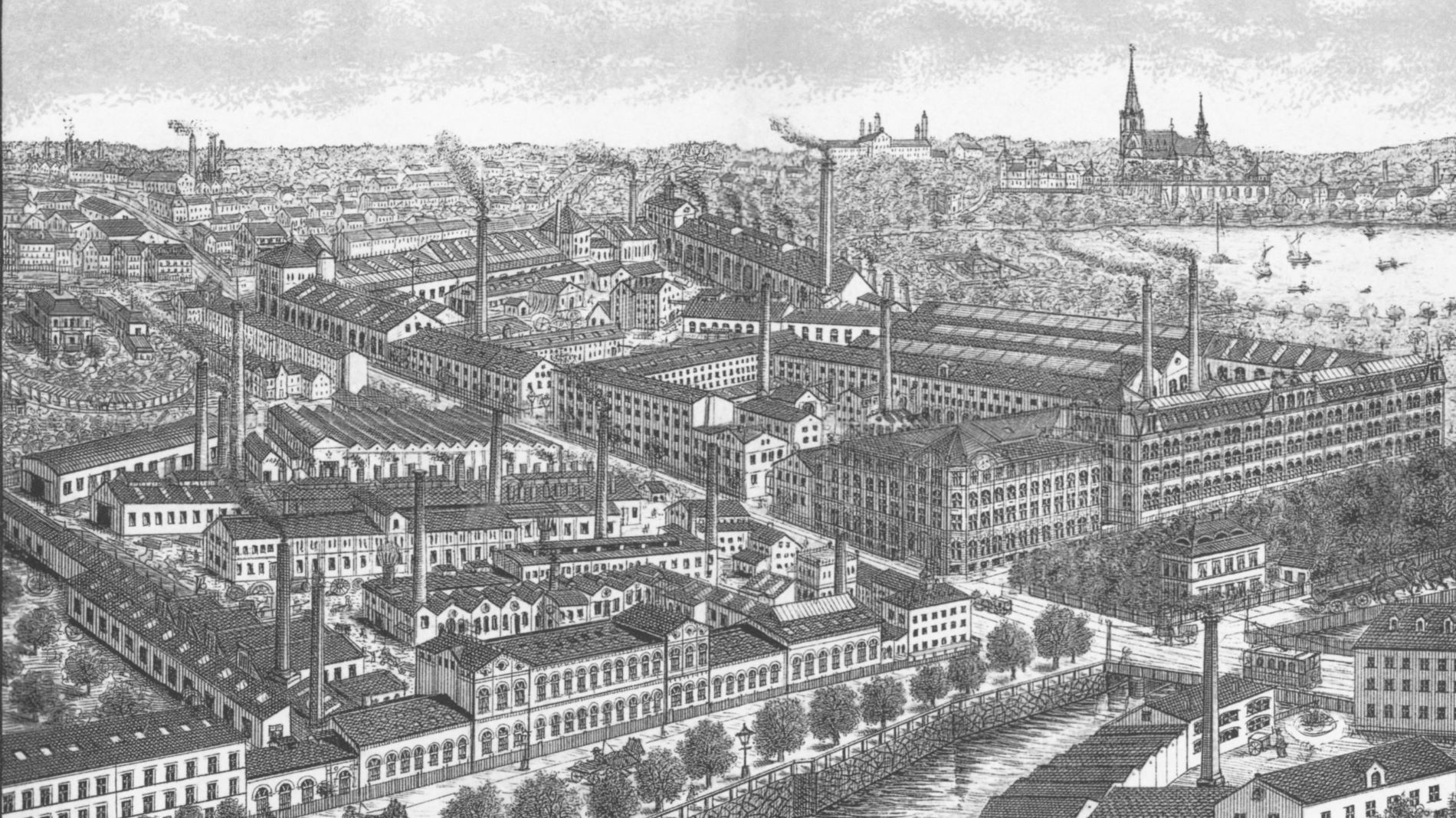

When the Industrial Revolution began in England around 1750, with the textile industry at its core, its momentum soon reached Chemnitz. As early as 1798, the first mechanical cotton spinning mill in Saxony was established in Harthau, now a district of Chemnitz. When Britain banned the export of textile machinery in 1820 to protect its technological edge, Chemnitz entrepreneurs simply began developing their own machines. Within decades, spinning mills, weaving plants and machinery firms flourished throughout the region. Textiles became Saxony’s most important economic sector, and Chemnitz emerged as the centre of Saxon textile machinery manufacturing. Fuelled by this textile dynamism, the once small town evolved into a European industrial metropolis, and by 1900 it was the richest city in Germany.2 Inspired by its English counterpart – the cradle of the Industrial Revolution – Chemnitz earned the nickname “Saxon Manchester.”

Textile heritage seeks a future

But those who explore the textile industry in this anniversary year of the “Saxon Manchester” encounter a mixed mood: pride in the past, yet uncertainty about the future. Chemnitz and the Saxon textile sector today encompass around 500 companies with some 12,000 employees and an annual turnover of €1.4 billion3, making Saxony one of Germany’s key textile regions. However, like the entire German textile and clothing industry, the region faces challenges: declining orders, rising costs, a shortage of young talent and questions about its future direction.

The Chamber of Commerce and Industry (IHK) Chemnitz summarised the situation in its Spring 2025 economic report4: “The Chemnitz region’s economy is in crisis.” A statistic on the training situation in the local textile and apparel sector is telling: across all training years in South-West Saxony, only 95 apprentices are currently in textile-related professions – out of over 3,500 apprenticeships in total (October 2025).5 In other words: just 3% of local apprentices are entering the textile field. A sector that once employed every third person in Chemnitz and served as the industrial heart of the region is clearly seeking new pathways.

Textile past and present at the Chemnitz Industrial Museum

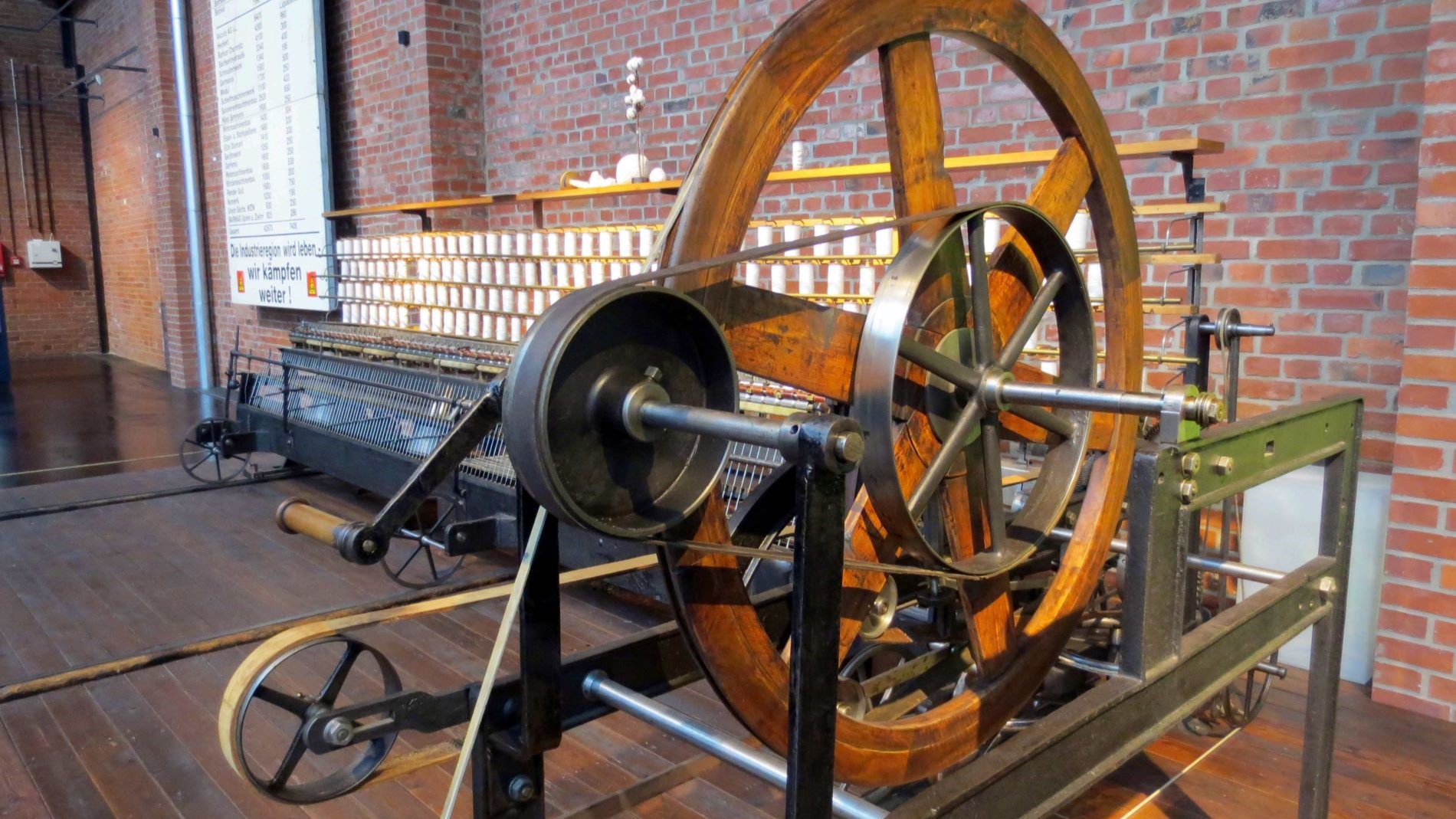

“The idea that Chemnitz’s textile industry belongs in a museum – we’re quick to dispel that,” says Anett Polig, deputy director of the Chemnitz Industrial Museum. Naturally, the museum honours the city’s textile heritage, for example in the “Textile Street” exhibition with its historical looms, knitting and spinning machines. But in the Capital of Culture year, the museum also wants to demonstrate that textiles in Chemnitz are not just history – they represent a future.

In partnership with the Association of North and East German Textile and Apparel Industry (vti), the museum curated the exhibition “Textiles? Future! 2025” (on display until 18 January 2026). Here, textile players from Chemnitz and its surroundings – including legacy firms, research institutes and start-ups – showcase the sector’s present-day diversity. Exhibits include colourful men’s shirts, designer underwear and knitwear, as well as snowboards made from hemp fibres, textile crane ropes, ground protection panels made of glass fibre composites, fabric-based packaging and textile bicycle spokes.

This eclectic mix exemplifies the transformation of the German textile and apparel industry, where textiles now account for 60% of the sector’s €20 billion annual turnover.6 “We want to show that the local textile industry is still alive, innovative and versatile,” says Polig. The exhibition is designed to provoke surprise: many visitors are unaware of the extent to which textiles are now used far beyond fashion. One particularly compelling example is the FFP2 mask, previously featured in regional textile exhibitions, with a backstory that traces back to the GDR era.

What does the FFP2 mask have to do with Saxon textile research?

Back in the 1960s, East Germany’s Scientific and Technical Centre for Technical Textiles (later the Institute for Technical Textiles, ITT) in Dresden was aiming to develop a jute substitute. The result was the polyamide-based spunbonded fabric “Kridee” – laying the technological foundation for the spunbond process. Despite difficult East–West trade relations, the company Reifenhäuser from Troisdorf near Bonn acquired the spunbond know-how at a Leipzig trade fair in 1974.7 Today a global leader in extrusion nonwoven and film equipment, Reifenhäuser refined the technology, added its own expertise and used it to develop its Reicofil spunbond lines. According to the company, 75% of all hygiene and medical nonwoven materials are now produced on Reicofil systems – including cover materials for nappies, feminine hygiene products and the now-famous FFP2 respirator masks that gained global prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve never signed so many NDAs as we do now”

“None of this would have been possible without Saxony’s know-how,” says Dr Heike Illing-Günther, Managing Director of the Saxon Textile Research Institute (STFI). “We still benefit from the legacy of our early nonwoven pioneers.” STFI was established in 1992 from the merger of the ITT, where the spunbond concept originated, and the Chemnitz Institute for Textile Technology (FIFT). Today, with around 150 staff and an annual turnover of €15 million, STFI is one of Europe’s leading applied textile research institutes. It continues the nonwoven legacy of its predecessor through its Nonwoven Competence Centre – which includes a Reicofil spunbond system sponsored by Reifenhäuser. Each year, STFI conducts around 100 projects on circular materials, textile lightweight construction, smart textiles and digital/AI-driven production – many in collaboration with textile companies and industrial partners worldwide. The names of these partners often remain confidential due to competition concerns. “We’ve never signed so many NDAs as we do today,” says Illing-Günther.

To counteract the invisibility of textile research caused by such confidentiality agreements, STFI has helped create two new public venues as part of the Capital of Culture programme. In partnership with the Esche Museum, the “Esche Lab” in Limbach-Oberfrohna and the “Textile LAB professional” at STFI have been established. Limbach-Oberfrohna has its own textile legacy: here, in the late 1940s, Heinrich Mauersberger developed the revolutionary Malimo stitch-bonding process in his garage – now used to produce technical textiles for cars, aircraft and wind turbines worldwide. In the two “maker hubs”, creatives, designers and artists can experiment with STFI’s advanced technology – from knitting and embroidery to warp knitting, weaving, 3D printing, laser processing and recycling.

At its Textile Lightweight Construction Centre, STFI is also working on forward-looking recycling methods – for instance, on ways to deal with the growing volume of carbon fibre waste from wind turbines and aircraft. Successfully so: in October 2025, STFI and the Fibre Institute Bremen received third place in the “Research and Science” category of the AVK Innovation Award for Fibre-Reinforced Plastics, for developing a method to reuse recycled carbon fibres in aerospace components.

Textiles from Chemnitz for Boeing and Airbus

What’s still under development in the STFI lab is already a reality at Dinghy Tech: fibres for the aviation industry. Based in Chemnitz and Zwickau, Dinghy Tech develops innovative textiles for aircraft, ships and medical applications. Founded in 2013 by Anton Schumann and Tobias Trommer, the company symbolises a new generation of Chemnitz and Saxon textile firms: small, agile and global players in technical textiles.

The name “Dinghy” was deliberately chosen. “It comes from English and refers to a small, light, manoeuvrable tender boat carried on larger ships,” explains Schumann. With Dinghy Tech, he and Trommer achieved what few manage: navigating the aviation sector’s complex, lengthy certification processes. “It was tough, but we did it,” says Schumann. Today, under the brand BLOCKSTA, Dinghy Tech’s flame-retardant seat cushions and textile interiors fly aboard aircraft from Boeing and Airbus.

“If you’ve flown with Lufthansa, Qatar Airways, United, Air Canada or Austrian Airlines, you’ve probably already sat on textiles from Chemnitz,” says Schumann. His conclusion after more than ten years in Saxony’s textile heartland? “I love Saxony,” says Schumann, a native of Munich who moved to the region in 2012 for love. “I firmly believe in the German textile industry – in both its heritage and its innovative strength, which are deeply rooted in Chemnitz and Saxony.”

Cover photo: University Archive TU Chemnitz/SLUB

1 https://www.chemnitz.de/en/our-city/history/industrial-history

2 https://www.chemnitz.travel/en/discover-chemnitz/industrial-culture/industrial-heritage-tour/industrial-heritage-history

3 https://business-saxony.com/en/a-business-location-at-its-best/strong-industries/kompetenz-in-textil

4 https://www.ihk.de/blueprint/servlet/resource/blob/6561660/7bade89b3fe719e110dc780dfbd8d706/konjunktur-fj2025-data.pdf (German)

5 https://www.ihk.de/chemnitz/servicemarken/presse/aktuelle-presseinformationen/presse-chemnitz/pm-05-ihk-chemnitz-veroeffentlicht-6419562 (German)

6 https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/256719/umfrage/umsatz-der-deutschen-textil-und-bekleidungsindustrie/ (German)

7 According to Der Spiegel (2021), the filter fleece used in modern FFP2 masks was first developed in the former GDR: “The nonwoven fabric used in today’s masks originates from a development in the East German chemical industry, which later became a successful export product.” — Der Spiegel, “Masken-Vlies für die Corona-Krise – später Exportschlager aus der DDR”, 13 February 2021.