Reading time: 6 minutes

When Hamburg's Wilhelm G. Clasen (WGC) natural-fibre trading company was founded in 1919, natural fibres accounted for almost 100 percent of the global fibre market. Since then, the market has changed beyond recognition. Today, natural fibres not only compete with synthetic fibres for market share but must also contend with downward pressure on prices, the consequences of climate change and new demands on their supply chains. At the same time, they are finding their way into a wide range of technical applications, including composites and drones. In this interview with Texpertise, WGC Managing Director Thomas Bressler talks about 100 years of natural-fibre trading, damaged natural-fibre cargoes, persistent industry myths and the future of the natural-fibre industry.

Mr Bressler, what exactly does WGC do – and how did you get involved with natural fibres?

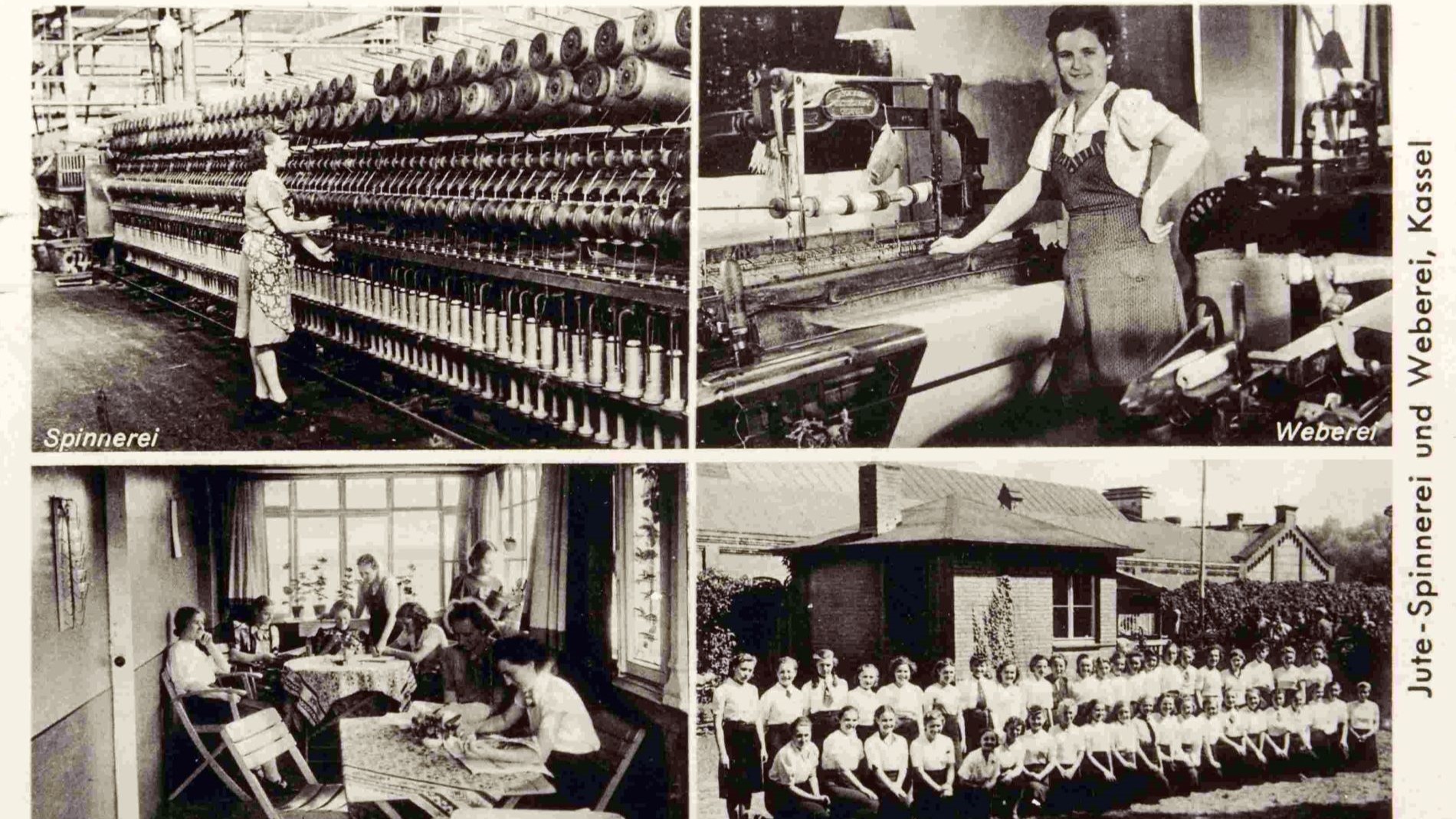

We act as an interface between individual farmers who grow natural fibres, manufacturers and consumers. WGC was founded in 1919 and began with raw jute, later adding kenaf and sisal. Today, our portfolio also includes abaca, hemp, cotton linters, kapok, coconut and niche fibres, such as pineapple and nettle fibres. We source our fibres from all over the world, including India, Bangladesh, Ecuador, Brazil, East Africa and Indonesia. We also work to raise awareness of the importance of renewable natural fibres. I used to work in the spice trade and my first contact with natural fibres was through jute bags for chillies. Then, when I joined WGC in 2011 and realised how complex this field is, I became fascinated with natural fibres. Even after more than 14 years, I'm still learning something new every day.

How has the trade in natural fibres changed over the last 100 years?

When WGC was founded, Europe still had a thriving textile industry that imported large quantities of raw natural fibres and processed them locally. Before 1914, Germany alone imported over 120,000 tonnes of jute every year. Over the years, many crises, such as hyperinflation, oil shocks and the Asian financial crisis, impacted the natural-fibre business. However, there were three main factors that changed everything: the switch from general cargo to container shipping in the late 1960s; the relocation of the textile industry to Asia; and the introduction of polypropylene in the 1950s/1960s, which led to a shift from natural fibre-based packaging materials to synthetic-fibre alternatives. This was more devastating than all the economic crises combined because it meant that a huge market for natural fibres was lost in one fell swoop.

What experience and insights has WGC gained in over 100 years of trading in natural fibres?

One key lesson is that there is a natural-fibre alternative for almost all applications – and sometimes even several – even though it used to be thought that only synthetic fibres were suitable. However, I would like to stress that the combination of natural fibres, recycled fibres and man-made fibres will be crucial if we are to meet the major challenges of the coming years and develop more sustainable products. This is why, if we are to be successful together, strategic partnerships were and continue to be of great importance in the world of natural fibres.

WGC has a special relationship with ‘damaged shipments’ – can you tell us more about this?

Damaged goods are natural fibres that originate from shipping accidents or have suffered transport damage. Our company founder Wilhelm G. Clasen and, subsequently, his son and successor Peter Clasen were adept at taking possession of salvaged cargo, processing it and reintroducing it to the market. This complex process involved sorting, drying and inspecting the goods to determine their suitability for alternative uses.

Which customers does WGC currently supply with natural fibres?

Our customer base reflects the wide variety of applications for natural fibres and ranges from small businesses to global corporations, from manufacturers of decorative items to pulp producers. We have been working with many of them for decades. However, we also have many new customers, including start-ups that develop natural-fibre composites for agricultural drones. However, there is one thing that all our customers have in common – a passion for natural fibres.

Which industries traditionally use natural fibres and where do you see the strongest potential for growth?

Traditional users who are still loyal to natural fibres include the rope and carpet industries and the packaging sector – coffee and cocoa beans, for example, are still packed in jute sacks, even though many products are now transported in container liners. Natural fibres also continue to be sold in large quantities for use in agriculture, for example, as harvest and binding twine.

“The most important growth market is probably the building-materials industry. Customers are already asking us to work on developments in which natural fibres are to supplement or replace synthetic fibres.“

Basically, however, I see a potential for natural fibres in all industries that want or need to improve their carbon footprint. The automotive, composites, pulp production, cosmetics and medical sectors are also becoming of ever greater interest.

How will the international market for natural fibres develop over the next few years?

The natural-fibre trade is in flux. In recent years, a large, future-oriented market has opened up for natural fibres, far removed from established areas of application. Much will depend on how successfully natural fibres can be incorporated into branches of industry that do not use them at present. If this goes well and general awareness of the need for sustainable raw materials remains high, I see a very positive future for natural fibres.

If WGC could share a single insight with the textile industry based on over 100 years of trading in natural fibres, what would it be?

Undoubtedly, it would be the fact that the natural-fibre industry has reinvented itself repeatedly over the decades – sometimes out of necessity but mostly driven by its own spirit of innovation. This ability to adapt in times of success as well as in difficult times demonstrates a high level of resilience and a raison d'être that will still exist a century from now.

Mr Bressler, thank you very much for speaking with us.