Reading time: 5 minutes

How did ‘Off the Grid’ come about?

Eva Benamou: Antonia and I met on a student exchange programme at ENSCI-Les Ateliers in Paris. I was studying product and industrial design, Antonia was studying textile design. I had a project in mind: to make a silk scarf with the help of a digital tool. Together we started an exchange of culture and knowledge about the two disciplines and realised the project.

Antonia Gauss: Bringing these two perspectives together was special for us, as they are usually separated in teaching. The interface between the disciplines made it possible to deepen the process, learn from each other and we really enjoyed working together.

“Bringing these two perspectives together was special for us, as they are usually separated in teaching. The interface between the disciplines made it possible to deepen the process and to learn from each other.”

How does the textile dyeing technique work with a pen plotter?

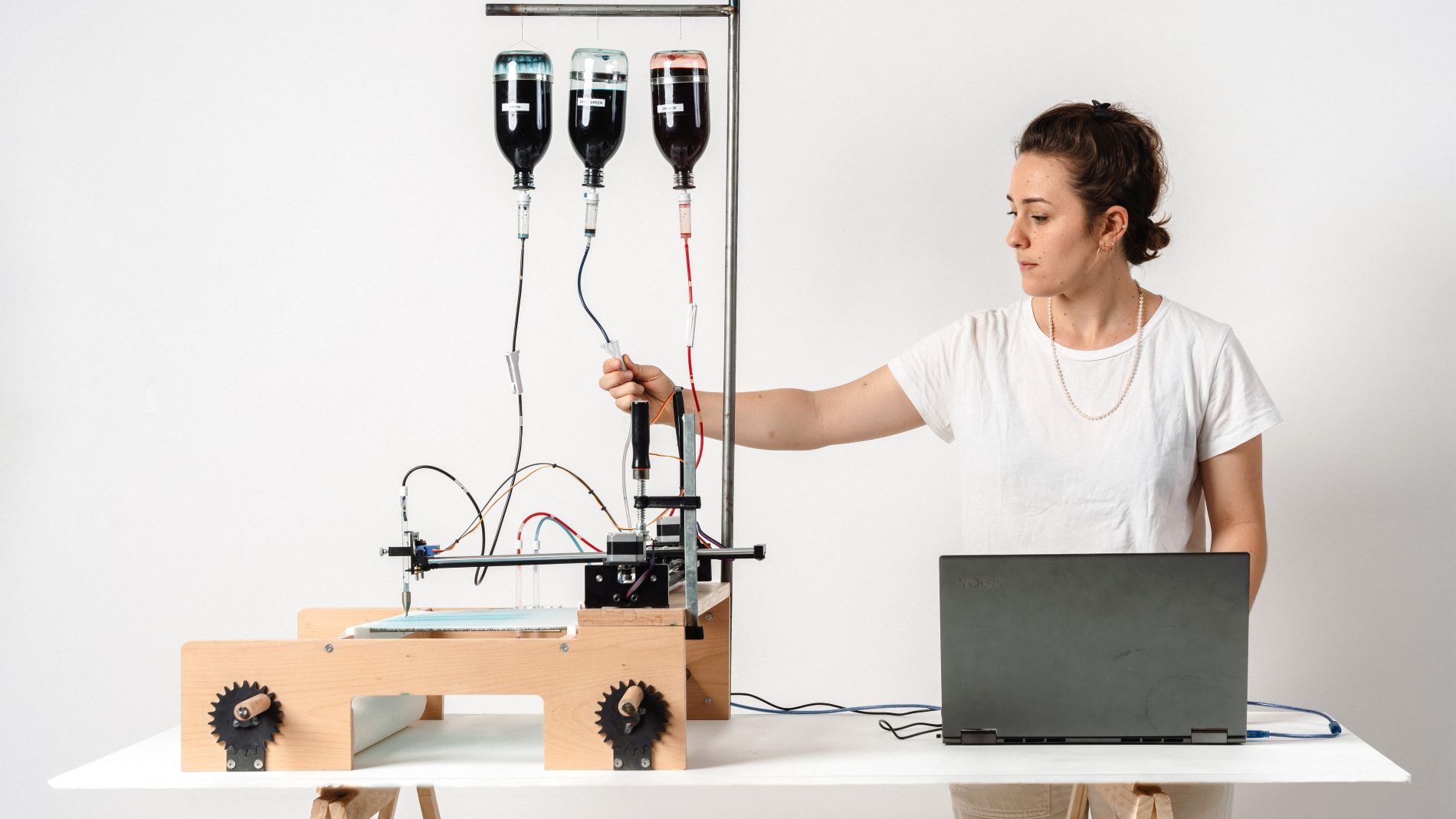

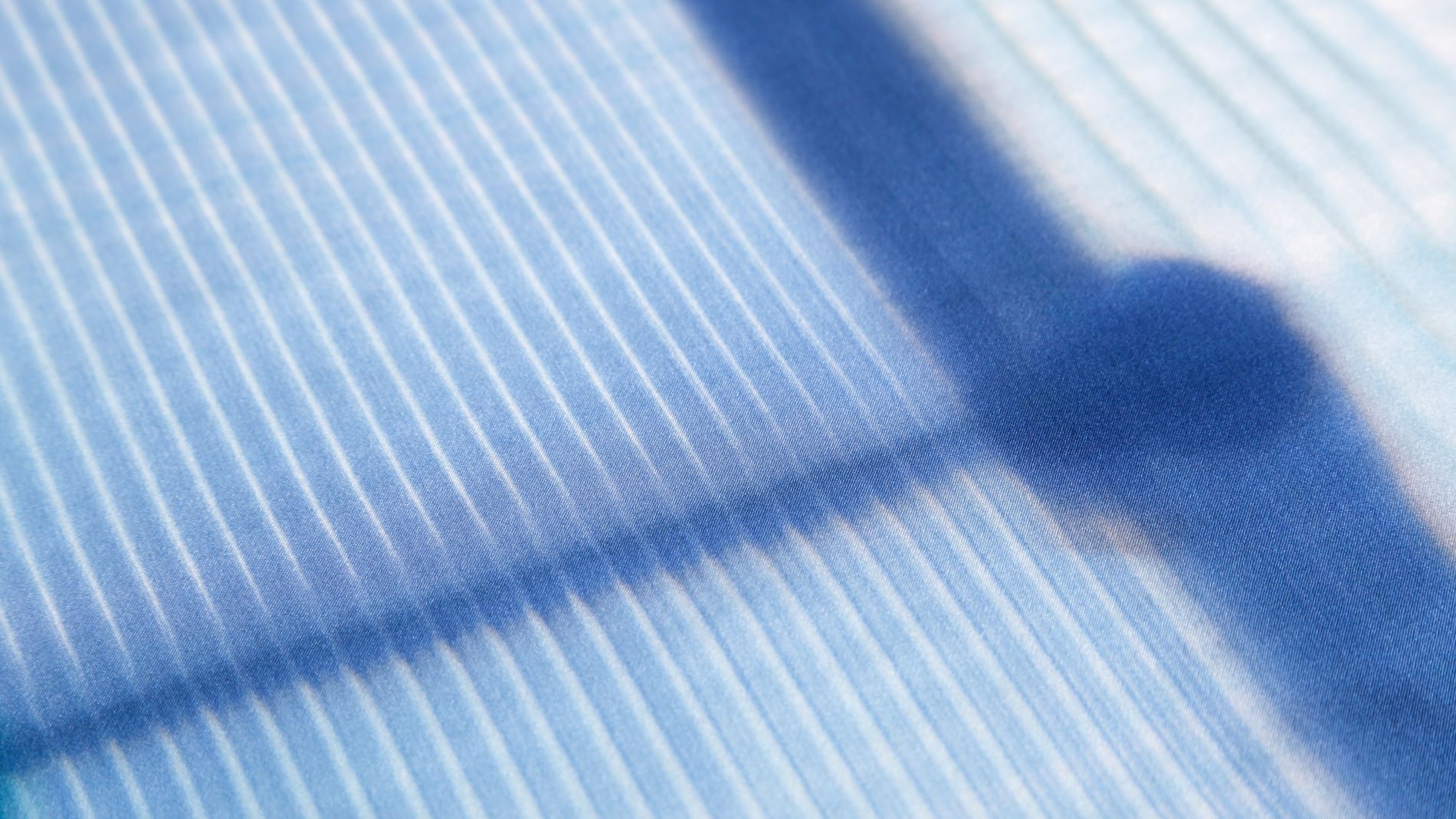

Antonia Gauss: Silk painting is an traditional craft that requires great manual precision and is rarely practised today. The pen plotter can fulfil the necessary fine details as a digital tool - the combination results in a new level of craftsmanship and technology. The development was experimental: the pen plotter actually serves as a drawing tool on paper, it is navigated using the x and y axes and visualises horizontal and vertical shapes such as curves. We started with simple structures on fabric and then developed our own dyeing system for it. In traditional silk painting, the fabric is stretched in bamboo sticks. This required some experimentation, as the fabric has to be stretched so that you can paint precisely on it. Inspired by the construction of the weaving loom, we developed a system on which the fabric is rolled up and stretched over a frame. the fabric can then be painted endlessly, repeat for repeat, in a stretched state. Mixing the colors was also a challenge because in most craft techniques, silk is dyed in a boiling dye bath in which the dye is heated and the fabric is placed in it. In our technique, we boiled the pigment in the dye bath and then let it cool before applying it to the fabric with our brush system. We also experimented with the ratio of liquid to colour and different fabrics. The result was particularly brilliant and even satin.

Eva Benamou: In this context, it was important to understand the requirements of the textile and the repetitive pattern and to adjust the machine accordingly. We were also inspired by the way kimonos are made in Japan. It's basically an almost endless piece of fabric with a repeating pattern. As part of our research, we were inspired by the Japanese philosopher Soetsu Yanagi to explore the meaning of what defines a pattern. He explains that a good pattern consists of three key elements: material, technology, and utility.

With this technology, did you have the opportunity to define patterns in advance or to control the result, or is it randomly generated during the process?

Eva Benamou: It's a combination of both. The colour, pattern and lines were defined in advance and up to five different brushes were developed in the process. We also created around 30 sketches for the system in order to precisely explore where the lines would run in the process. We interact with the machine, but control the pattern and the brush movement via the connection between the plotter and the computer. The randomness arises in the distribution of the amount of colour. The pressure with which the brush moves downwards with the pen plotter always remains the same.

Antonia Gauss: We also wanted the visual outcome of the pattern refers to the printing process and the interaction between the hand and the machine. The flow of the color is regulated by hand, leaving irregular floating points that give the design its unique character. The prints tell in a way the story of the printing process and are equally reminiscent of digital and analog processes.

Would you say that the technology you developed could be transferred to an industrial scale?

Eva Benamou: Yes, absolutely. The machine is currently set to a fabric size of 40 centimetres, as in the production of fabric panels for a kimono. However, the x and y axes can also be extended. Currently, Off the Grid is an experiment and offers the option of continuously printing a length of fabric. Technically, however, there is still a lot of room for manoeuvre.

Antonia Gauss: I am sure that it would be possible to produce the process on a larger scale, as the plotter is a CNC machine that is very easy to build.

Can you tell me something about the composition of the colours?

Antonia Gauss: We used pigment based acid dyes that are used for protein fibres such as silk or wool. After dyeing, the textile is fixed in a steam tube and the dye is absorbed into the fiber, so the colour remains brilliant on the textile.

To what extent was sustainability an issue for you?

Eva Benamou: The project was divided into two sections: An experimental part and a theoretical part. It is important that we as designers understand what we are doing and why. One of our inspirations was the manifesto on textiles by Li Edelkoort. It's not just about using sustainable materials but also about making young consumers and designers aware of the history and importance of textiles.

Antonia Gauss: The textile industry is going through a difficult phase, as the demand for cheap production and favourable prices is high. All the more reason for us to look back to the roots of craftsmanship, to a high-quality process that is carried out with care and precision, and to transfer this to the present day using the latest technologies. The responsibility also lies with customers to become aware of what they are buying. Our aim is to promote an awareness and appreciation of textiles and to scrutinise how they are produced.

“It's not just about using sustainable materials but also about making young consumers and designers aware of the history and importance of textiles.”

Which area of design would you like to work in over the next few years?

Eva Benamou: I'm still trying to find an answer to this question. There are many questions that interest me and are closely linked to the influence products have on our society. Currently I'm working at Naoto Fukasawa Design Office as a designer and am grateful for the opportunity to explore and gain a deeper understanding of how small details in objects have the power to shape our daily lives.

Antonia Gauss: I recently started an internship at the textile company Jakob Schlaepfer in Switzerland. As a designer with a passion for textile technology, my personal interest is in textile machines, the connection between creation and technical realisation and the balance between them.